Knee arthritis

‘Arthritis’ is generally taken by most people as a term to describe ‘wear and tear’ or ‘degeneration’ in a joint, where the joint becomes ‘worn out’. However, what does this actually mean?

Knee anatomy

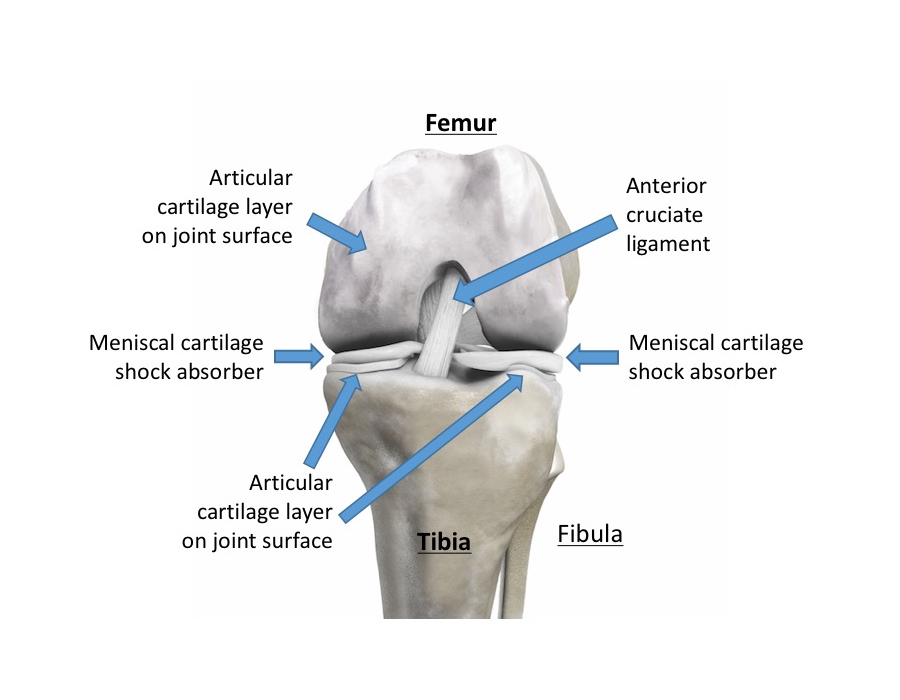

The surfaces of the ends of the bones in a knee joint are covered in a thin, white, glistening layer of smooth tissue called ‘articular cartilage’. The articular cartilage makes the joint surfaces smooth and low-friction, so that the joint can move through literally millions of movement cycles per year with, normally, little or no wear. Indeed, articular cartilage actually has the lowest coefficient of friction (i.e. it’s the slipperiest) of any substance known to man!

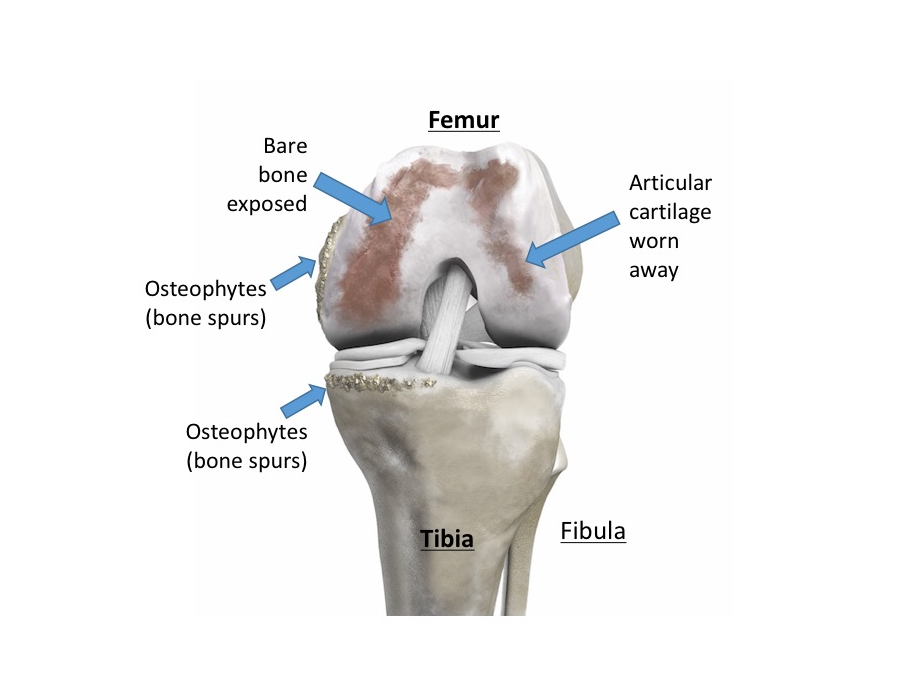

When it works well, articular cartilage is amazing stuff: it can withstand forces that are multiples of body-weight with 1000s and 1000s of impacts. However, articular cartilage does not have any blood supply, and the cells within the tissue are relatively metabolically inactive. Therefore, if articular cartilage is damaged then it tends not to repair itself, and any wear and tear simply tends to be progressive and cumulative, until eventually the cartilage layer wears away altogether. If the damage is only minor (partial thickness), then we tend to refer to this as just ‘wear and tear’. However, if the cartilage loss is full-thickness, with actual bare bone exposed, then this is fully-blown arthritis.

Types of knee arthritis

There are different types of arthritis, and it is worth being aware of this:

- Primary Osteoarthritis: this means degeneration and loss of the articular cartilage due to simple ‘wear and tear’. This is often just simply part of the natural aging process. However, there is often a genetic component to this, and osteoarthritis can often tend to run in families. Also, with primary osteoarthritis there is often involvement of multiple other joints, such as both knees, the hips, the base of the thumb and the finger joints.

- Secondary Osteoarthritis: this is where the arthritis develops as a result of previous damage to a joint, from things such as trauma (fractures, ligament tears, meniscal cartilage tears) or from infection in the knee (septic arthritis). Secondary osteoarthritis tends to occur primarily just in one isolated joint (where there has previously been an issue) as opposed to it being a more widespread and generalised joint problem.

- Inflammatory Arthritis: there is where the lining of the knee (the synovial membrane) becomes inflamed, and the joint becomes red, hot, swollen and painful. This can occur in just one isolated joint, or it may affect multiple joints around the body. This inflammation is seen in conditions such as Rheumatoid Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis, which are auto-immune conditions. Joints can also become inflamed from ‘metabolic’ problems, such as gout, which is where irritant urate crystals develop inside a joint. With persistent inflammation, one often tends to get softening and then damage of the articular cartilage damage in the joint, which can then lead to secondary osteoarthritis developing.

The symptoms of knee arthritis

Knee arthritis tends to cause:

- pain,

- swelling and

- stiffness in a knee.

The pain tends to be a deep dull achy toothache type pain that is normally worse with prolonged activity, such as long walks, and towards the end of the day, particularly if you’ve been on your feet a lot.

If there are also sudden sharp pains or ‘mechanical symptoms’, such as painful clicking, catching, locking or giving way, then this can indicate that there might also be a meniscal cartilage tear in the knee or potentially some unstable or loose cartilage in the joint (a loose body), in addition to the arthritis.

Non-surgical treatments for knee arthritis

If you have just minor symptoms and your knee isn’t too bad, then you might be able to manage your symptoms ‘conservatively’ (i.e. without surgery), with just painkillers / anti-inflammatories and activity modification (i.e. just avoiding whatever it is that specifically aggravates your knee).

Other potential non-surgical treatments for early knee arthritis include:

- physiotherapy

- off-loading knee braces

- intra-articular joint injections.

Importantly, however, one shouldn’t really talk about treatments until one has first got a clear and specific diagnosis! – and this means having a proper, full, detailed assessment of your knee.

Go see a specialist!

There is no better specialist when it comes to knees than a Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon who specialises specifically and purely in just ‘knees’! One shouldn’t be put off by the word ‘surgeon’ – in my practice I only tend to operate on less than 25% of the patients that I see in clinic: the other 75% are simply happy with either just a diagnosis, or ‘education’ and a detailed explanation of what they’ve got and what their options might be, or they might simply need any one (or any combination) of the various non-surgical treatment options available. However, seeing someone who fully understands all of the different pathologies that can be found in a knee, who can fully interpret your imaging, and who has a full understanding of all of the pros and cons of each of the different potential treatment options available is key.