Realignment Osteotomy

Most people have got relatively straight legs (neutral/normal alignment). However, malalignment is common. Malalignment can cause increased wear and tear in a knee and can lead to arthritis. Alternatively, progressive malalignment can develop with time as a knee becomes increasingly arthritic.

It is essention to check a patient’s lower limb alignment angles prior to considering surgical procedures such as meniscal transplantaiton, articular cartilage grafting or Biological Knee Replacement, and alignment (and whether it is fixed or correctable) is also an important factor contributing to the decision as to whether a partial knee replacement might be a potential option instead of a total.

Surgical correction of ‘deformity’ (malalignment) can also be a very useful potential surgical treatment for reducing knee pain, keeping a knee going for longer, and for delaying the time when knee replacement surgery might actually end up being required.

What is lower limb alignment?

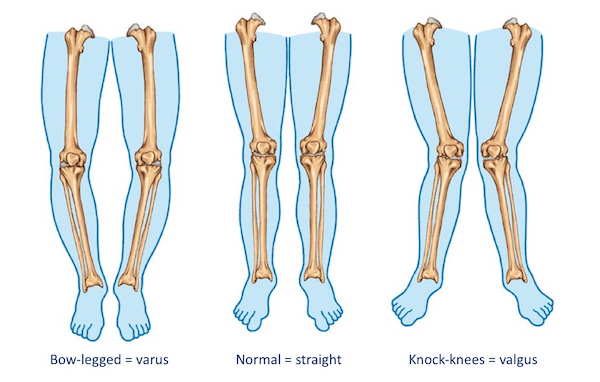

If your legs are nice and straight, then this is called ‘neutral alignment’.

If you are ‘bow-legged’ (i.e. your knees are wider apart than normal whilst standing) then this is referred to as varus malalignment.

If you are ‘knock-kneed’ (i.e. your knees are closer together than normal or even touching whilst standing) then this is referred to as valgus malalignment.

With a varus knee, increased pressure is placed on the inner (medial) side (compartment) of the knee joint.

With a valgus knee, increased pressure is placed on the outer (lateral) side (compartment) of the knee.

The importance of imaging

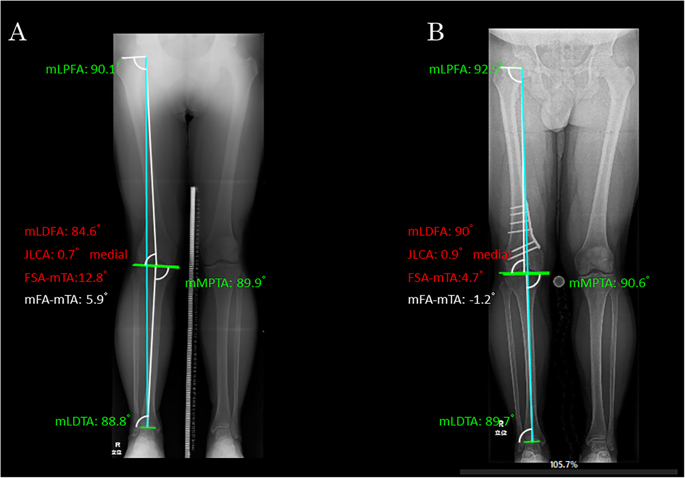

Importantly, the only way to properly check for lower limb alignment is to get long-leg weight-bearing alignment X-rays, and these need to be done using a special X-ray ‘plate’. These give views of both legs with the patient standing, and show everything from the pelvis (with the hip joints), both knee joints and down to the ankles joints.

From these X-rays it is possible to measure a variety of different angles on the bones, which allows your surgeon to quantify the exact number of degrees of any potential deformity, and this is critically important if you are even contemplating any potential kind of realignment surgery.

Medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy

The most popular surgical technique for correcting a knee with a varus deformity is to perform a medial opening wedge proximal tibial realignment osteotomy. This is also often referred to as an ‘HTO’ (a high tibial osteotomy).

HTO involves making an oblique cut in the bone at the top of the tibia and then correcting the angle of the leg, which opens up a wedge-shaped gap on the inner side of the bone. This gap is then filled with bone graft (usually bone allograft, i.e. processed donor bone) or an artificial bone substitute (which acts as a scaffold for new bone to grow into), and the bone is then held with a metal plate and screws.

Lateral opening wedge distal femoral osteotomy

The most common type of osteotomy to correct a valgus knee is a lateral opening wedge distal femoral realignment osteotomy (often referred to as a DFO (a distal femoral osteotomy).

DFO involves making an oblique cut in the bone at the lower end of the femur and then correcting the angle of the leg. This opens up a wedge-shapred gap on the outer side of the bone. Just like with HTO, with DFO the gap is filled with bone graft (usually allograft or artificial bone substitute) and the bone is then held with a metal plate and screws.

What's actually involved with the surgery?

Realignment osteotomy is fairly significant surgery… The surgery is normally performed under a general anaesthetic (although it can be undertaken under a spinal, if needed), and it normally takes about 1 hour or so. Most people stay in hospital for 1 night post-operatively, before then leaving the hospital the following day.

The osteotomy needs to be protected for the first few weeks whilst the bone is healing, and we therefore normally keep people on crutches and in a knee brace for the first 6-week period, although physiotherapy rehab treatments are commenced after the first week or so.

It normally takes most people somewhere between 3 to 6 months to feel that they have recovered fully from the actual surgery itself, and then maybe another 3 months or so for them to get their fitness levels back up.

What are the outcomes of osteotomy surgery?

The results of realignment osteotomy surgery depend very much on the age of the patient, the amount of deformity and the state of the knee (i.e. the degree of degeneration / arthritis). In an appropriate patient, osteotomy can have success rates in the region of about 90% at 10-year follow-up. Importantly, however, ‘success’ is a very arbitrary term, and the figures depend very much on the actual definitions used. Most published studies define ‘failure’ as the need to progress to knee replacement surgery, in which case it can be said that: after realignment surgery, only about 10% of patients have needed to go ahead with knee replacement surgery within 10 years.

How can I predict whether an osteotomy might help me?

One good way of checking whether or not an osteotomy might be a suitable option for your knee is to try using an offloading knee brace first. These braces are heavy-duty robust strap-on braces that ‘crank’ the knee sideways to offload whichever side of the knee is damaged (in a knee where the damage is either solely or predominantly on just one side (medial or lateral) of the joint). They are worn anytime you know that you are going to be on your feet for long periods, such as walking outdoors. Not everyone can actually get on with wearing a big clunky knee brace, but they’re a lot less pain, hassle and risk than having an osteotomy. Importantly, if a knee brace works, then:

- the patient may decide that that’s all that they actually need, and they may not need to go ahead with any actual surgery for the time being,

- some people might decide to stick the use of the brace and avoid any surgery altogether, for good, and

- if wearing the brace works, then this gives a very good indication that realignment osteotomy is likely to be effective.

CLICK HERE to read more about the role of knee braces in arthritic knees.

What are the risks of osteotomy surgery?

Realignment osteotomy surgery is not something to be taken lightly, as it involves pain, hassle, time off work and time to recover, and although the success rates are generally good, a positive outcome can never be guaranteed. Importantly, as with all surgery in or around the knee, there are specific risks of potential complications, and these include:

- nerve or blood vessel damage

- blood clots

- infection

- non-union (failure of the bone cut to heal)

- ongoing pain.

On top of this, if the patient does eventually end up having to have knee replacement surgery, then the metal osteotomy plate and screws will need to be removed first – this means the patient having to undergo an extra additional operation for removal of the metalwork. Some surgeons recommend removal of the osteotomy metalwork relatively early on, at about 12 to 18 months after the initial osteotomy surgery, once the bone has 100% healed and remodelled. This is because the longer the metalwork is left in, the harder it can end up being to remove it (as sometimes new bone can grow over the plate and the screw heads).

Finally, there is some evidence that the results of knee replacement surgery might potentially be slightly poorer in those patients who have previously undergone knee osteotomy surgery.

The ideal candidate...

The ideal candidate for realignment osteotomy surgery is someone with:

- significant enough varus or valgus malalignment of their knee,

- the patient should be sufficiently symptomatic to justify the negatives of surgery,

- the damage in the affected side/compartment (medial for a varus knee, lateral for a valgus knee) should not be too severe (i.e. too far gone),

- the condition of the other/opposite compartment of the knee should be normal or close to normal (i.e. this is not an appropriate treatment option for someone with widespread arthritis in their knee), and

- normally, the patient would be ‘young’, meaning that they are considered too young for actual knee replacement surgery.

The older a patient is over about 50, the more sensible it is to consider going straight for a partial knee replacement rather than an osteotomy (i.e. just the one op instead of potentially three! – 1 op for the osteotomy, a second op for removal of the metalwork and then potentially a third op for an actual knee replacement sometime later in the future.

Book an assessment

CONTACT US if you would like to arrange an appointment with a full assessment of your knee.